LANGUAGES

Dialect is a distancing device. Others speak in

dialect. You don't. I don't.

The characters in Ama speak Konkomba,

Dagbani, Asante, Fanti, Dutch, Susu, English, Yoruba, Portuguese. I convey all

this in straight English, trying to show mutual incomprehension through context.

My one exception is the Liverpudlian seamen on

the slave ship. With them I deliberately use dialect as an ironic distancing

device. Usually it is the 'natives' who speak in dialect. Not so in this case.

But how did they speak in Liverpool in the late eighteenth century and how does

one convey their speech in writing? I could find little help on this issue ( not

even in Lynda Mugglestone's 'Talking Proper,' The Rise of Accent as Social

Symbol, Clarendon, 1997) and so I fell back on invention based on Cockney,

with dropped and added aitches.

My agent advised that I was overdoing it. I

compromised by simplifying my invented orthography, leaving out most of the

apostrophes. Here's an example.

" Ere, Fred, eres a loikly

un fer yer," said Joe Knox as he dragged Ama up over the lee gunwale,

"Got a bit of flesh on er, this un as."

Ama thought that she heard

English, but the pronunciation was so strange that she could not make out the

meaning of the words.

"Stan up straight

now, an les get a look at yer," he ordered.

Bewildered, Ama did as she

was told. She looked around her. Before her stood the tall main mast,

stretching up into the sky. Stays and rigging ran out from it in all

directions.

"Nice pair o

tits," said Joe.

"Ere Fred, look at this

uns boobs," he called, weighing each of Ama's breasts in a palm.

"What dye think, eh?"

Ama stepped back and gave

him an angry look; but she let the English profanity which rose to her throat

die on her lips. Her mind was beginning to work again. It would be better if

these white men did not realize that she understood their language. She took

her wet cloth and rewrapped it under her armpits.

"Okwaseá.

Foolish man," she spat out at him in Asante.

"Knox,

stop foolin around," called the Bosun from the quarterdeck, cutting short

Joe's reply.

Does it work?

========================================================================================

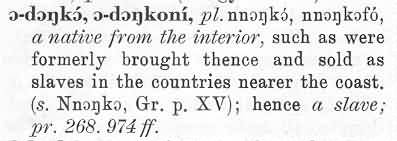

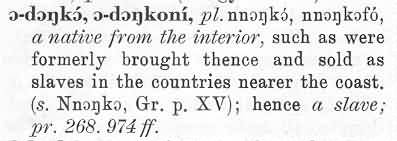

Myers Robert A, Bibliography of works in

Ghanaian languages Bureau of Ghana Languages 1967 incl Konkomba

Christaller, Rev. J. G, Dictionary of the

Asante and Fante Language called Tshi (Twi), Second Edition, Basel, 1933

This dictionary is a gem, a rich museum of Akan culture. Publication of a new

edition is long overdue. Project Christaller 2001 (Akan encyclopedic

dictionary), a cooperative effort of the University of Zurich, Switzerland and

the University of Ghana, is addressing this need. For more information

click on http://www.unizh.ch/spw/afrling/akandic/

and, about Christaller, the man: http://www.akan.org/akan_cd/ALIAKAN/course/U-References-p210.html

Ali

Akan 2000, "African languages through internet" at http://www.unizh.ch/spw/afrling/aliakan/

promises publication shortly of a CD-ROM version of an experimental on-line

course in Akan. Material from the CD-ROM is available on-line at the following

link.

Akan

Teleteaching Course (free, on-line, highly recommended) http://www.akan.org/akan_cd/ALIAKAN/start.html

Authors:

Bearth, Thomas: (PhD) Professor for General Linguistics and African Languages and

Linguistics at the University of Zurich, Thomas_Bearth@compuserve.com

Eichholzer,

Erika: (lic.phil. I) Research assistent at the

University of Hamburg in a socio-linguistic project on "Twi in Hamburg:

Language maintenance/language loss in an unstable social situation". Akua.Erika@hamburg.de

Frempong,

Justin: (B.A.) Bible translator with GILLBT (Ghana

Institute of Linguistics, Literacy and Bible Translation), Justin_Frempong@sil.org

Hirzel, Hannes: (dipl. El. Ing. ETH and lic. oec. publ.) EDP consultant, Hannes_Hirzel@compuserve.com

The West Africa 7 font for Windows is

available for download at http://www.unizh.ch/spw/afrling/aliakan/toc.html

Shoebox Software, http://www.sil.org/computing/shoebox/Software.html,

also offers a free download of fonts which can handle the special Akan letters, Ń,

Ď and Ç,

but I have taken the easy way out, using e, o

and n. My

transcriptions, using OCR, of parts of Christaller's preface and introduction,

should therefore be treated with reserve. MH

Preface to Second Edition

The first edition

of the present work - commonly called ‘The Tshi Dictionary’ - published in

1881, has for a number of years been out of print. As the book was much in

demand by both Europeans and educated natives, it was decided that a new edition

should be issued. Unfortunately, financial difficulties, the uncertainty

concerning a new script, and an accident which befell the editor, delayed its

appearance.

The Dictionary is

based on the Akuapem dialect, which was reduced to writing about 1838, and

became afterwards the literary form.

The material

consists, for the most part, of the contents of the former edition. To these

have been added numerous words, meanings, and phrases gathered from the printed

Tshi literature and from manuscripts; also contributions sent in by Rev. A.

Jehle, and the Editor's linguistic collection which he brought home with him

from the. Gold Coast. The greater part of this material as well as the original

work has been revised here with the assistance of Rev. D. E. Akwa. In

order to keep price and size of the book within moderate limits, not all the

material available has been inserted. For the same reason some of the Appendices

also have been omitted.

Of the Akuapem

dialect not many words will be found wanting; which cannot, however, be said of

the other dialects. Regarding this deficiency, and in other respects as well,

there is still room left for improvement.

The different

dialects have, as far as possible within the limits, found consideration. Words

more or less local and not yet in general use, have, as a rule been marked as

such by indicating the dialect to which they belong (i.e. by placing initials

after the words).

A word or

expression styled obsolete in one district may be still in use in another.

The use of the

words in sentences is illustrated by definitions, expressions from daily life,

proverbs &c. Being contributed by natives, all these examples are idiomatic,

presenting the genuine manner of expressing thoughts. For further illustration

the collection of proverbs and other books . . .

are frequently referred to.. . .

Introduction.

§ 1. Name and

Territory of the Language.

Tshi, or Twi, is the language prevalent in the Gold Coast countries

between the rivers Asini and Tanno on the W. and the Volta on the E., and

extends even beyond this river; its southern boundary is the sea-coast, while

the upper course of the Volta, and the Kong mountains are its northern limits.

That is, roughly, the area of the old Asante empire when it had its greatest

extension. Formerly Guang dialects were spoken throughout the Gold Coast, but in

the course of time they were, in most places, superseded by Tshi. - The number

of people who speak Tshi may be estimated at about 2 millions; and the language

is steadily gaining ground.

Twi, rarely Etwi

or Otwi, is the form used in the vernacular. It is pronounced like ‘Chwee’,

ch and w being uttered simultaneously. The vowel i has a rising and falling

tone, thus: î or íě. Twi probably denotes ‘polished, refined’; from twi,

to rub, polish. The form ‘Tshi’, (a modification of the older spellings Tyi,

Oji, Otyi), is, as a rule, employed in English. - Another name of the language

is Akan . . ., probably meaning ‘foremost; genuine’; from

kan, first; e.g. oye Okanni, he is

a born or genuine Tshi man. ‘Akan’ is used in a wider sense (a) for the

dialects of Akem, Asante, Adanse &c. . . ., and (b) in a narrower for those

of Akem and Asante only.

The name ‘Twi’

being used not only by the natives themselves, but also by the Accras and tribes

to the east of the Volta, (in the form ‘Otshui’), it has been retained as

the generic appellation of the language. . . .

§ 2. Dialects.

The dialects

which have found consideration in the Dictionary, may be comprehended under the

following three names: 1. Akan, 2. Bron or Kămănă, 3. Fante.

1. The Akan

dialect is considered to be spoken purest (a) in Akem; but by its “dainty and

affected mode of expression” . . . it appears less suited to become the common

dialect of all Tshi tribes. - (b) The dialect of Asante agrees in all essentials

with that of Akem, only the pronunciation is “broad and hard”. . . whilst in

Akem it is “soft and delicate”. . . . (c) The dialect of Akuapem, derived

from Akem and Akwam (an Akan dialect of old standing) and having points of

contact with Bron and Fante, became about 1842 the literary form intelligible to

all the other tribes. It. has ever

since been enriched by words and grammatical forms from the other dialects. . .

3. The Fante dialects, spoken by several maritime tribes in the South,

have not followed the other dialects in changing the initial sounds kw, gw, hw,

before palatal vowels, into tw, dw, fw, and in occasionally softening b (esp. in

diminutives . . .) into w &c., but have deviated from them by changing t, d,

n, before (e), e, i, into ts, dz, ny, (which change had not yet taken place in

1764, when Ch. Protten published a short Fante Grammar at Copenhagen), and by

curtailing many terminations by cutting off their final vowels. They seem to

differ more from all the above dialects and among themselves than the Bron

dialects do from Akan. The Fante dialects are a branch of the Akan language, but

are not acknowledged as pure by the Akans. As regards the number of people who

speak Fante and the territory where it is spoken, it is far surpassed by Akan.

As already

observed, there are many differences (in sounds, forms, and expressions) within

the three groups of dialects, but they are not so great as to prevent people of

the one group from understanding readily those of the other. . .

§ 3. The Position of

Tshi among other West African Languages

and a short

Survey of the latter.

Tshi is one of

the Sudanic languages prevailing in the area between Senegal and Eastern

Nigeria. These languages may be divided into the following groups: -

1. The so-called

Kwa group, spoken in a broad coastal tract from the middle of Liberia to the

lower Niger. Its subdivisions and languages (or dialects) are:

a) The Ewe-Tshi

subgroup, viz. Ewe (including the Dahomey dialect), spoken in the south-

eastern corner of the Gold Coast east of the lower Volta, and in the southern

half of Togo and Dahomey; and Tshi, i. e. the Akan-Fante dialects. Other

members: Nzema (in Apollonia) and Doma (north-west of Asante); Anyi, Baule and

Afema (Ivory Coast); Anufo (Northern Togo). The Ga, or Accra language, a

comparatively young dialect, and the cognate and older dialects of Adangme and

Krobo, W. of the lower Volta and in some parts E. of it. The Guang dialects,

spoken on the Gold Goast and in Togo. -

b) The Lagoon (or

Kwakwa) languages, on the lagoons of the Ivory Coast. -

c) The Kru

subgroup, on the western Ivory Coast and the coast of Liberia. –

d) The Yoruba

subgroup, in Nigeria. -

e) The Nupe

subgroup, in Northern Nigeria. -

f) The Ibo

subgroup, on both sides of the lower Niger. -

g) The Edo or

Bini subgroup, in Southern Nigeria.

2. The Benue

& Cross River group. To this belong e. g. Efik-Ibibio and Okoyong.

3. The Central

Togo group, e. g. Adele, Akposo, Kebu. -

4. The Gur group,

approximately between 5o E. & 5o W. long., and 8o

& 14o N. lat. Some of the subdivisions and languages are:

a) The Mosi

Dagomba subgroup comprising e. g. Mosi, Dagomba (Dagbane), Mamprusi, Gbanyang

(Gondja). -

b) The Grusi (Gurunsi)

subgroup, between the White and the Black Volta: Awuna (Atyulo), Sisala,

Kanjaga. -

c) The Tem

(Hausa: Kotokoli) subgroup, in eastern Togo. –

d) The Bargu or

Borgu (Barba), in northern Dahomey and Togo. -

e) The Senufo

(Siena) subgroup, on the northern Ivory Coast. -

5. The West

Atlantic group, south of Senegal, with two subgroups, including e. g. Temne,

Bulom, Gola; Wolof, Serer. -

6. The Mandingo

or Mande languages, spoken in western Sudan, between the two last-named groups,

and north of the western parts of the Kwa group. They may be subdivided

into

a) Mande tan,

comprising e. g. Bambara, Malinke, Dyula, Vai-Konno; and

b) Mande fu,

including Soso, Mende, Kpelle. . . .

§ 4.

Characteristic Features of the Tshi Language.

The great

majority of Tshi words are monosyllables, consisting of one consonant and one

vowel, the latter sometimes enlarged, by the addition of a nasal consonant or a

‘w’. There are, however, also a considerable number of polysyllables which

cannot be reduced to monosyllabic stems.

Tshi has three

classes of words only, viz. nouns, pronouns and verbs. But even these, when

without affix, are not always distinguishable by their form. Part of the

adjectives, adverbs and conjunctions are derived from nouns or verbs. Instead of

English prepositions, either nouns of place or various verbs are used as

postpositions. The passive voice and participles are wanting. There is no

inflexion in the strict sense of the term.

Cases are distinguished by their position in a sentence or expressed by

verbs or postpositions. The plural of nouns is formed by affixes or indicated by

a verb. The grammatical gender is wanting; natural sex is in some cases

expressed by particular words, or by composition with such, or by the female

diminutive suffix. For the tenses and other modifications of the verb prefixes

(partly recognised as verbs) are used, in two cases the suffix e or i.

There is only a

scanty number of particles to indicate the relation of sentences, or clauses, to

one another. In many cases the sentences are placed together without a

conjunction; (co-ordination being more frequent than subordination). In a

similar manner, two or several verbs may follow each other, where the English

language uses a single verb or adjective, participle, adverb, or preposition.

The natives analyse every action or occurrence into its component parts, and

express each of them by a special verb.

Another peculiarity is the use of subordinate sentences defined by the

definite article ‘no’, or the demonstrative ‘yi’; whereby they are

indicated to be equivalents of a single noun representing one idea.

There is to be

found a large number of onomatopoetics, of which most are used as descriptive

adverbs, several also as nouns.

The vowel-harmony

(i.e. assimilation of vowels to neighbouring vowel sounds) provides against too

great or too small dissimilarities of vowels in successive syllables.

The nouns have

prefixes, which do not form such distinct classes of nouns as are found in Bantu

languages, but still convey some classification of persons as opposed to things,

and of single or individual as opposed to plural or collective existence.

Of great importance

for the understanding of the language is its intonation. Every syllable of every

word has its own relative tone or tones, equal with or different from the

neighbouring syllables, being either high or low, or middle. Besides this

intonation, inherent in the original formation of words, there are also ‘grammatical’

tones, by means of which different tenses are denoted.

Akan Bibliography

http://www.isp.msu.edu/AfrLang/Handbook/Akan-bib.htm

And another Akan Bibliography

http://www.indiana.edu/~librcsd/afrlg/data/0016.html

Akan Literature

Akan

Shakespeare:

Julius

Caesar, translated into Twi by B. Forson Accra 2001 ISBN 9988 591 00 4

Bu me Be, Akan

Proverbs, Peggy Appiah, Kwame Anthony Appiah with Ivor Agyeman-Duah, Accra,

2002? ISBN 9988-8120-0-0

7015 Akan proverbs, each

with a literal translation into English and an explanation.

Examples:

2003. Odonko po bebrebe a,

yede no ko ayie.

If a slave becomes too

familiar we take him to a funeral custom.

(In the old days slaves

were sacrificed at funerals to go with the departed spirit into the next world.

If someone abuses their position, they are removed.)

2004. Odonko nsiesie ne ho

se ne wura.

A slave does not dress

like his master.

(You must show due decorum

in your behavior and not try and act above yourself.)

![]()

![]()

![]()