- 292 . . . Significant

numbers of the Brazilians began to arrive in West Africa in the first

decades of the nineteenth century. In 1835 an uprising of the black

population - slave and free - in Salvador, Bahia, shook the authorities

so much that they took measures forcing many ex-slaves to leave for West

Africa. Local authorities placed severe restrictions on people of

African descent, including fines and deportations of those who in any

way were “suspected of trying to provoke slaves into

insurrection." Under these restrictions, many freed Africans left

seeking a more congenial life elsewhere. Many eventually came to West

Africa, which they regarded as home. Thus, the Brazilian community in

Accra, after whom a street is named (Brazil Street) in James Town, dates

its arrival to this period (1836).

Throughout the nineteenth century, more immigrants continued to come as they acquired freedom and money to pay their passage. The final abolition of slavery, which occurred in Brazil in 1888, provided another impetus for ex-slaves to migrate to West Africa. Many of those who had been sent to Brazil as young people nurtured the remembrances of their homes in Africa and longed to return. The total abolition of slavery opened the way for them to attempt to fulfill this longing. Many thus found money and boarded ships coming to the West African coast . . .

-

EDWARD M. BRUNER is Professor Emeritus, Department of Anthropology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801

(Abridged; published with the permission of the copyright holder, the American Anthropological Association. I should like to acknowledge Prof. Bruner’s strong support for my attempt to obtain permission to republish his paper here unabridged. Prof. Bruner is not responsible for this abridgment, which cannot do justice to the original.)

-

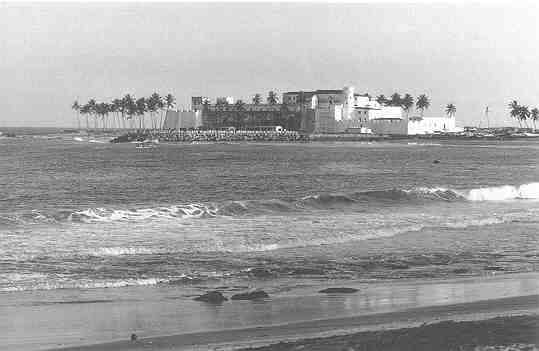

Figure 1: Elmina Castle. Photo by Edward M. Bruner

My essay (describes) the meeting in the border zone between African American tourists who return to mother Africa, specifically to Elmina Castle on the coast of Ghana, and the local Akan speaking Fanti who receive them.

In 1993, there were 17,091 visitors to Elmina Castle; 67 percent were residents of Ghana, 12.5 percent were Europeans, and 12.3 percent were North Americans. An important and growing segment consists of blacks from the diaspora, and includes many African Americans.

The Struggle over Meaning

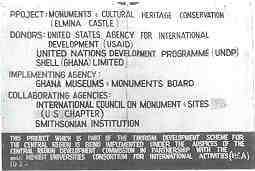

As part of the tourism development project, much effort has gone toward the rehabilitation of the historic castles and the construction of a museum in Cape Coast Castle. The increased attention has precipitated discussion over the interpretation of the castles, particularly over which version of history shall be told.

What most Ghanaians want from tourism is economic development, including employment, new sources of income, better sanitation and waste disposal, improved roads, and a new harbor.

While Ghanaians see tourism primarily as a route to development, the African American tourists have a different perspective.

African Americans focus on the dungeons at the 500-year-old Elmina Castle because, understandably, the slave trade is of primary interest to them. Indeed, many African Americans come to Ghana in a quest for their roots, to experience one of the very sites from which their ancestors may have begun the torturous journey to the New World. It is for them a transition point between the civility of their family in Africa and the barbarism of slavery in the New World.

For many African Americans, the castles are sacred ground not to be desecrated. They do not want the castles to be made beautiful or to be whitewashed. They want the original stench to remain in the dungeons. . . Some diaspora blacks feel that even though they are not Ghanaians, the castles belong to them.

Balancing this sadness is the sense of strength and pride many African Americans feel at the recognition that their ancestors must have been strong people to have survived these inhuman conditions.

Most Ghanaians, on the other hand, are not particularly concerned with slavery.

Generally Ghanaians focus on the long history of Elmina, while diaspora blacks focus on the mid-Atlantic slave trade, which reached its height between 1700 and 1850. Ghanaians want the castles restored, with good lighting and heating, so they will be attractive to tourists; African Americans want the castles to be as they see them - a cemetery for the slaves who died in the dungeons' inhuman conditions while waiting for the ships to transport them to the Americas. Ghanaians see the castles as festive places; African Americans as somber places.

Conflicting Interpretations

Which story shall be told? Vested interests and strong feelings are involved.

The Representation of Slavery

The attention of diaspora blacks to the dungeons and the slave experience has the potential consequence of introducing into Ghanaian society increased tension between African Americans and Ghanaians, and possibly a heightened awareness of black-white opposition, a sensitive and possibly controversial issue. . .

The situation is full of ironies. When diaspora blacks return to Africa, the Ghanaians call them obruni, which means "whiteman'' . . .

Many Ghanaians have told me that they consider some African Americans to be racist.

. . . an African American tourist who meets a Ghanaian may secretly wonder, Did his ancestors sell my ancestors? Further, some Ghanaians, seeing that diaspora blacks are prosperous and educated, feel they were in a sense fortunate in being taken as slaves, because now they are economically well off and have a higher standard of living than the Ghanaians. African Americans too may ask, What would my life have been like had my ancestors not been taken as slaves but remained in Africa?

- Who Owns the

Castles?

Aside from the issue of representation and interpretation, there is the question of who should control the castles. The Ghana Museums and Monuments Board is the designated custodian of all national monuments, but traditional chiefs also have a claim

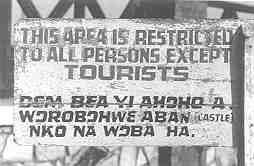

One Elmina resident, refusing to pay the entrance fee, stated that the castle and the land belonged to the Elmina people, so why should they pay an admission fee? Some African Americans also refuse to pay the fee, saying they didn't pay to leave here, so they shouldn't have to pay to come back.

So who "owns" the castle? Who has the power to represent one of Ghana's greatest historical monuments?

Figure 3: Juneteenth celebration, 1994, Cape Coast Castle. Photo by Edward M. Bruner

Figure 4: Elmina Castle and surroundings, view from the town. Photo by Edward M. Bruner

Tourism as Commerce Ghanaians generally welcome tourists but . . .

Figure 5: Sign by the entrance to Elmina Castle. Photo by Edward M. Bruner

Cultural Revival

A final consequence of tourism is that the tourist interest in Ghanaian culture has led to an increase in Ghanaians' own interest in their culture.

Final Thoughts

In conclusion, we ask again, who owns Elmina Castle - the diaspora blacks who left as slaves, the Elmina citizens and the traditional chiefs who remained in place, the USAID and other international aid agencies who support the restoration and provide the interpretive perspective, or the tourists to whom the castle has now been dedicated?

Figure 6: Sign on the grounds of Elmina Castle. Photo by Edward M. Bruner.

This is a rhetorical question, but the castle has not been simply a passive place. Elmina Castle may have been built initially as a European colonial intrusion on the Guinea Coast, but subsequently the castle has made its own claims to power and monumentality. Dominating the countryside, a massive structure on the edge of a humble fishing village, the castle takes on properties of its own and imposes its own meanings on the surrounding area. Elmina Castle is a bastion of power, a site to be struggled over, a transition point between the passage of goods and peoples from the interior of Africa to Europe and the New World. Old castles have long histories, stories of combat and battle, honor and degradation, beauty and cruelty, civilization and barbarism. Who owns the castles? Who has the right to tell their story?

Mahdi, Adamu The Hausa Factor in West African History ABUP OUP

- 134-5 Also significant in attracting other Muslims form the interior before the influx of the interior traders in the second half of the nineteenth century was the settlement at Accra of a sizeable number of liberated African slaves from Brazil. Some of them were said to have been received and accommodated by the chiefs of Accra, including Chief Ankrah. AA Brown gives the names of the following as accommodated by Chief Ankrah (they were either Muslims before or during slavery) Malam Aruna, Usuman Kangidi, Mamam Nassau, Peregrino, Zugger Mascino, Alu Mama and their Imam Malam Mama Sokoto. How many of these people were Hausa cannot be said though at least the Imam was. AA Brown has dated their arrival at Accra to c 1836 though he has given no indication as to how he arrived at the date.

- The

history of slavery, the slave trade, abolition and emancipation [SLAVERY@LISTSERV.UH.EDU]

Re: Brazilian returnees to the Gold Coast

From: IN%"plovejoy@yorku.ca" "Paul Lovejoy" 16-NOV-1998 08:06:39.21

There is a considerably greater bibliography on returnees, including from Brazil, than in Parkvall's bibliography, and there is a lot of research currently underway on the topic. The leading authorities on the subject are Bellarmin Codo, Elisee Soumonni, but Kristin Mann's work on Lagos and Robin Law's work on Ouidah is also significant in tracing individuals.

From: Pat Manning, Northeastern University manning@neu.edu

In addition to the sources listed by M. Parkvall on Brazilians on the Slave Coast, the most thorough is J. Michael Turner's dissertation, "'Les Bresiliens': the Impact of former Brazilian slaves upon Dahomey" (Boston University, 1975).

Two important theses including information on Brazilians in 20th-century Dahomey are:

Sylvain Anignikin, "Les origines du mouvement national au Dahomey, 1900-1939" (these de 3e cycle, University of Paris VII, 1980).

Bellarmin Codo, "La Presse dahomeenne face aux aspirations des 'evolues'" (these de 3e cycle, University of Paris VII, 1978).

In addition, my analysis of the economic history of Dahomey traces, if concisely, the role of Brazilians in economic and political affairs of the region from early 19th to mid-20th century.

Manning, Slavery, Colonialism and Economic Growth in Dahomey, 1640-1960 (Cambridge, 1982)